A power supply suitable for use with the 60W amplifier presented in the predeeding project is perfectly simple, and no great skill is required to build (or design) one. There are a few things one should be careful with, such as the routing of high current leads, but these are easily accomplished. The first thing to choose is a suitable transformer. I suggest toroidal transformers rather than the traditional "EI" laminated types because they radiate less magnetic flux and are flatter, allowing them to be installed in slimmer cases.

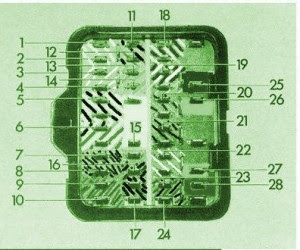

They do have some problems, such as higher inrush current at switch on, which means that slow blow fuses must be used. For the 60W amplifier, a nominal (full load) supply of +/- 35V is required, so a 25-0-25 secondary is ideal - however, see Updates, below. The circuit for the supply is shown below, and uses separate rectifiers, capacitors and fuses for each channel. Only the transformer is shared, so channel interactions are minimised. A single ±35V supply (i.e. using only a single bridge and set of filter capacitors) will work just as well in the majority of cases.

The 5A slow-blow fuse shown is suitable for a 300VA transformer, if a 120VA transformer is used, this should be reduced to 2.5A (or 3A if 2.5A proves too hard to get). If you are even a little bit concerned about the fuse rating, contact the transformer manufacturer for the recommended value for the transformer you will use. The correct fuse is critical to ensure safety from electrical failure, which could result in the equipment becoming unsafe or causing a fire.

The capacitance used is not critical, but is somewhat dependent upon ones budget. I suggest 10,000uF capacitors, but they are rather expensive so at a pinch 4,700uF caps should be fine - especially in the arrangement shown. When unloaded (or with only light load), the voltage will normally be somewhat higher than 35 Volts. This is Ok, and should not cause distress to any amp. The voltage will fall as more current is drawn, and may drop below 35V if a small transformer (or one with unusually poor regulation) is used.

Two parts of this circuit are critical:- Mains wiring must be cabled using approved 240V rated insulated cable, and all terminations must be insulated to prevent accidental contact. The mains earth must be securely fastened to the chassis, after scraping away any paint or other coating which might prevent reliable contact.

- The centre-tap of the transformer and the ground points of each capacitor must be connected to the main signal earth point via heavy duty copper wire, or (preferably) a copper bus-bar. Large currents flow in this part of the circuit, containing nasty current waveforms which are quite happy to invade your amplifier. The supply voltages must be taken from the capacitors (not the bridge rectifiers) to prevent unwanted hum and noise.

When wiring the bridge rectifiers to the transformer, connect exactly as shown to ensure that ripple voltages (and currents) are in phase for each amp. If not, mysterious hum signals may be injected into the amps signal path from bypass capacitors and the like. This is somewhat unlikely unless huge caps are used on the amp board(s) - not recommended, by the way - but why take the risk?

Bridge rectifiers should be the big bolt-down 35A types (or something similar) to ensure lowest possible losses (these will not require an additional heatsink - the chassis will normally be quite sufficient). The transformer primary voltage will obviously be determined by the supply voltage in your area (i.e. 120, 220 or 240) and be suited to the local supply frequency. Note that all 50Hz transformers will work just fine at 60Hz, but some 60Hz devices will overheat if used at 50Hz.

The transformer should be rated at a minimum of 120VA (Volt-Amps) for home use, but a 300VA transformer is recommended due to its superior regulation. Going beyond 300VA will serve no useful purpose, other than to dim the lights as it is turned on. Where it is possible, the signal and power ground should be the same (this prevents the possibility of an electric shock hazard should the transformer develop a short circuit between primary and secondary. Where this will give rise to ground loops and hum in other equipment, use the method shown.

The resistor R1 (a 5W wirewound resistor is suggested) isolates the low-voltage high-current ground loop circuit, and the diodes D1 & D2 provide a protective circuit in the event of a major problem. These diodes need only be low voltage, but a current rating of 5A or greater is required. The 100nF capacitor (C1) acts as a short circuit to radio frequency signals, effectively grounding them. This should be a device with very good high frequency response, and a monolithic ceramic is recommended.

Updates:The transformer secondary voltage will probably need to be higher than described above. I tested some stock and custom transformers I have, and found that unless the transformer has extraordinarly good regulation, a nominal 28-0-28 secondary will be needed, more with an average (i.e. poor) regulation unit. Also be careful when you test, since a relatively small (10%) variation in the mains voltage makes a big difference to measured output power - the secondary voltage also falls by 10%, so 60W becomes 48W if the mains is 10% low.

You also need to remember that the output voltage of transformers is typically quoted at full power with a resistive load. This means two things:

- The no load voltage will be higher than expected

- The loaded voltage will be lower than expected

The first point is true because there is no loading, so the output voltage must rise. The second is more complex, but happens because the conventional rectifier circuit uses a capacitor input filter (the rectifier feeds directly into the capacitor(s)). Since the diodes only conduct at the peak of the waveform, the current is much higher, so the transformer and supply line impedance will cause the peak voltage to fall, and the DC voltage cannot exceed the peak output voltage (less two diode forward voltage drops).

Source: http://sound.westhost.com/project04.htm

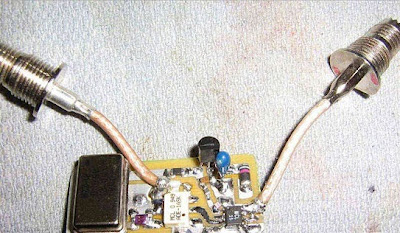

This proved to work excellently with Philips equipment, and it will probably also work with equipment from other manufacturers with a few small modifications. Voltage regulator IC1 is used here to allow the supply voltage to range from 8V to 30V, and diode D1 provides protection against a reverse-polarity supply voltage connection. A nice side benefit arose from the fact that the loudspeakers in question (Conrad models) have transparent cones and protection grilles with rather large openings. This made it possible to fit the tiny circuit, which was built on a piece of prototyping board, to the frame of one of the speakers, behind the cone. The whole arrangement is thus hidden, but the remote control still works perfectly if it is aimed towards the speakers.

This proved to work excellently with Philips equipment, and it will probably also work with equipment from other manufacturers with a few small modifications. Voltage regulator IC1 is used here to allow the supply voltage to range from 8V to 30V, and diode D1 provides protection against a reverse-polarity supply voltage connection. A nice side benefit arose from the fact that the loudspeakers in question (Conrad models) have transparent cones and protection grilles with rather large openings. This made it possible to fit the tiny circuit, which was built on a piece of prototyping board, to the frame of one of the speakers, behind the cone. The whole arrangement is thus hidden, but the remote control still works perfectly if it is aimed towards the speakers.